ESPLANADE HOTEL, PERTH (1898-1972)

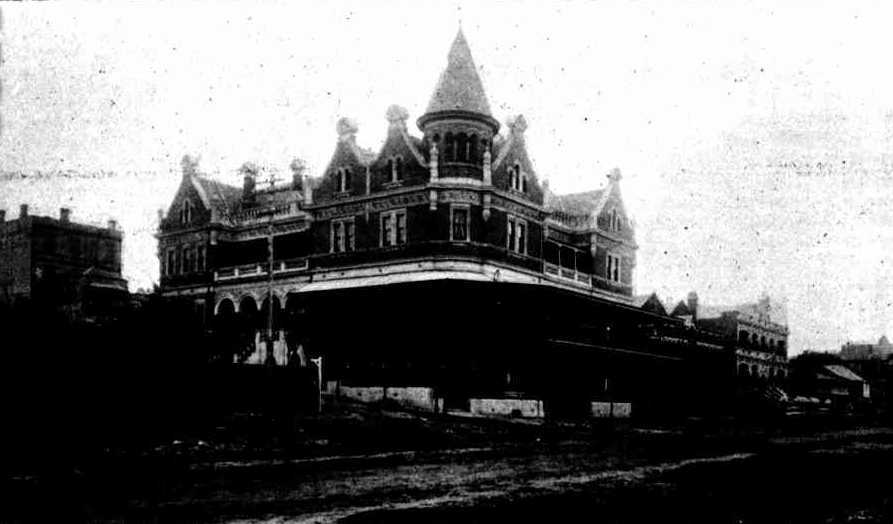

The Esplanade Hotel, on the corner of Bazaar Terrace (now the Esplanade) and Howard Street, was designed in 1897 by architects and brothers Michael Francis and James Charles Cavanagh of Messrs M F and J C Cavanagh (later Cavanagh and Cavanagh), for mining entrepreneurs Nathaniel White Harper, Esq (32) and James Ross MacKenzie (40), who was also a director of Emu Brewery. They were partners in the hotel until MacKenzie, who had been in ill-health for some time, died in 1915 aged 58, after which Harper bought out MacKenzie’s share.

Building tenders were called for in January 1898 and, after a successful bid by architect and builder Charles Oldham, was complete by November. One of four new hotels built in Perth that year, the Esplanade was said to be the most beautifully-appointed in the colony.

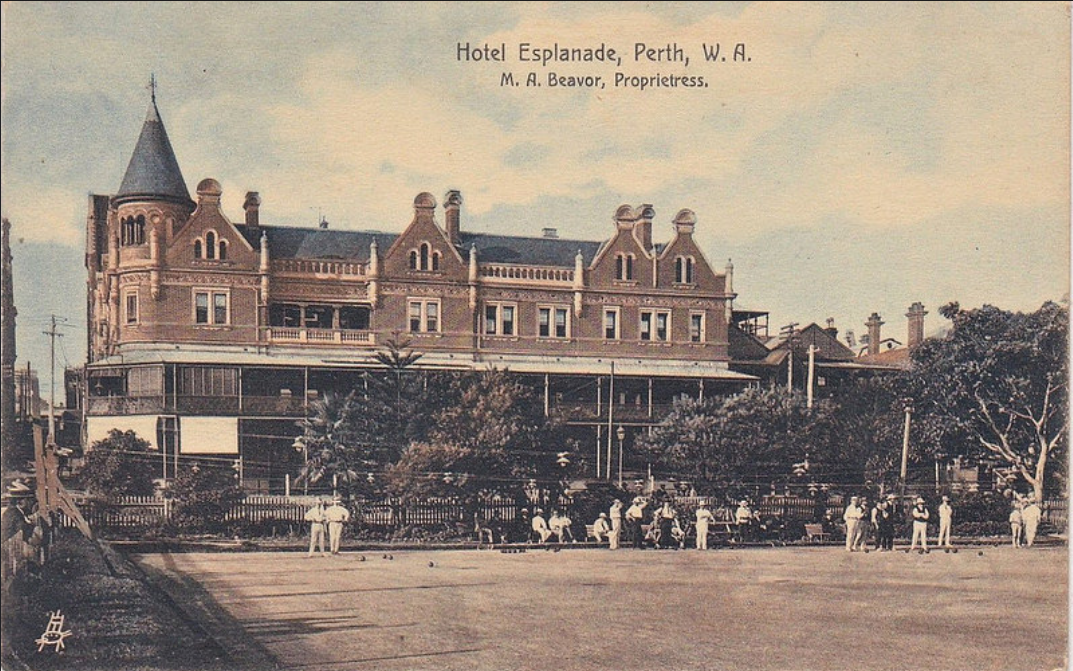

Superbly situated on, and facing the Esplanade, it caught the fresh river breezes and was directly opposite the bowling green and tennis courts. Built with striking red bricks superbly contrasted with crisp white window moulding and intricate interior panelling, its design also featured a magnificent tower on the corner, from which guests could take in breathtaking views of the Swan and Canning Rivers, Melville Water and Crawley.

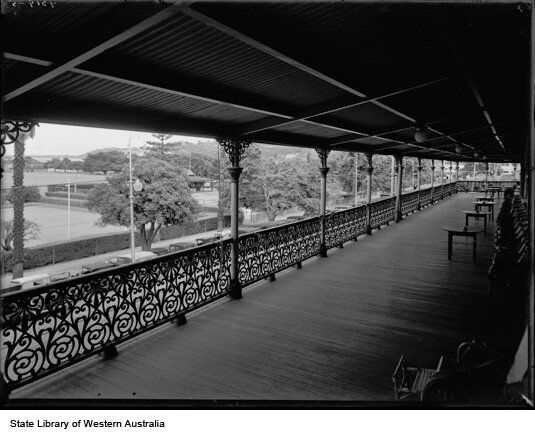

The three-storey, 41-room hotel included six sitting rooms, 25 guest rooms and living quarters for the licensee. It was constructed in modern Renaissance style with Cavanagh’s typically substantial, broad verandahs on which to promenade or rest. Replete with every modern convenience, the Esplanade was recognised as WA’s best hotel for more than 50 years.

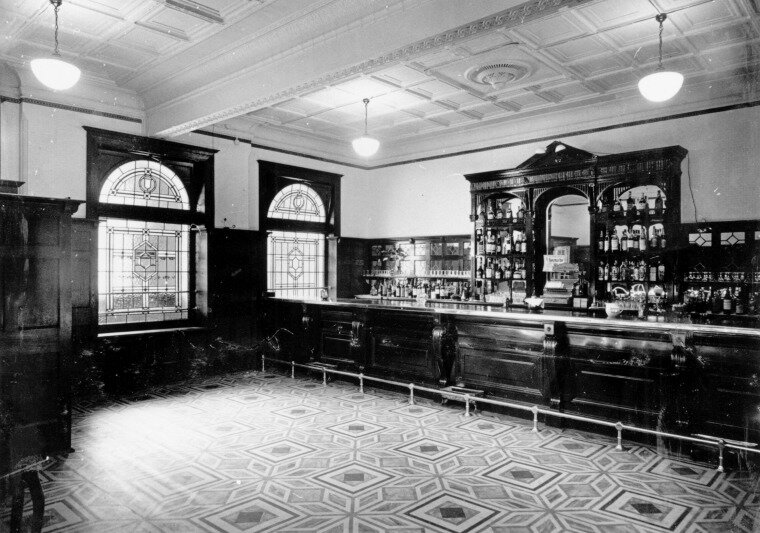

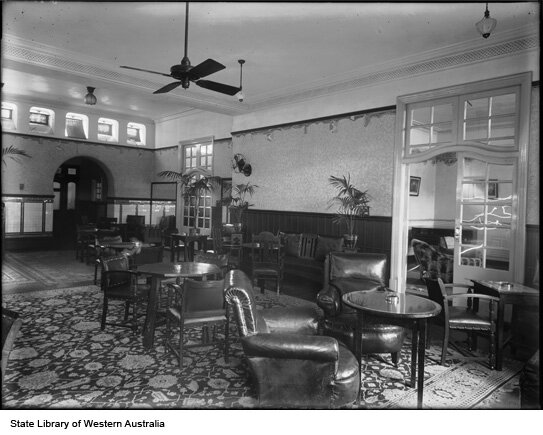

The entrance to the ground floor saloon, partly underground, was on the corner with access from either street. Inside was a spacious hall with a buffalo-hide lounge and plenty of comfortable chairs and tables. Off the hall the parlour, commercial room and anterooms were luxuriously furnished with ornate mantelpieces, handsome sideboards, a piano, and the same buffalo-hide armchairs in which patrons could relax. A favoured watering hole of workers from the Atlas Assurance Building and others nearby, the gentlemen often stood with their backs to the bar, watching ladies’ legs as they walked past on their way down Howard Street.

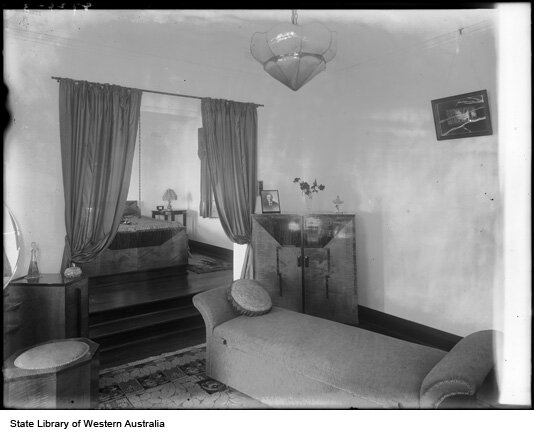

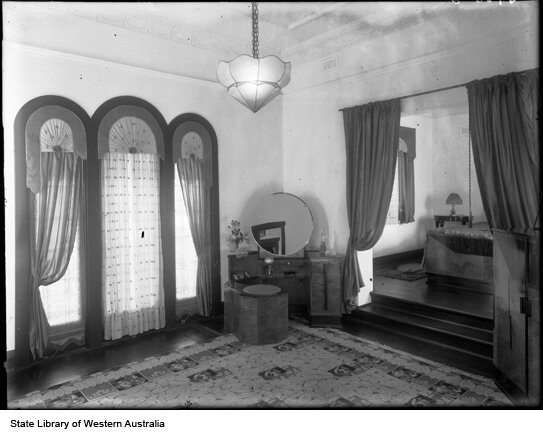

A broad, grand staircase led to the first floor accommodation of luxuriously appointed single and double bedrooms, each with high quality imported furniture from Messrs Robertson and Moffat, and French doors opening onto the verandah overlooking the river. Also on the first floor was a spacious reading room with lounges and comfortable chairs, and the drawing room, said to be ‘splendidly appointed’ with chairs that looked as if they were made of bronze and delicate china paintings on the walls. Both rooms opened onto the first floor verandah through French doors. The building cleverly took advantage of the steep slope of Howard Street, from which patrons could directly enter the dining room and the billiard room, also on that level.

The second floor accommodation was similar to the first, with some rooms opening onto balconies. A ladies’ sitting room on this floor was as beautifully furnished as the rest. The Esplanade was the first Perth hotel to have private bathrooms and many rooms had one.

The Esplanade’s first licensee was Harry Folk, who oversaw the hotel’s first, glittering wedding reception held on Monday 12 December 1898, after the society marriage of well-known, Irish-born solicitor Francis Harney (32) and his young bride Gladys Canning (nearly 19) at St Mary’s Cathedral.

The second licensee, from 1903, was Maud Beavor (44). She was a widow and mother of one son, Norman (then 18), and had experience managing the Oriental Hotel in Melbourne and the Shamrock Hotel in Bendigo, Victoria, but had never been a licensee. As she had been in Victoria, she was quickly recognised here for her superb hostessing talents and generosity of spirit; perhaps too generous, as she was charged several times for serving beer on a Sunday!

Considerable changes to the hotel were made in 1910 when Harper contracted original builder Charles Oldham, then in architectural partnership with Alfred Cox in Oldham Cox, in conjunction with John Smith, for a significant three-storey extension of the east wing which almost doubled the hotel’s frontage onto the Esplanade. Construction began in February at a cost of £1,200 and when complete, matched seamlessly with the existing building.

At Christmas 1916, Beavor heard the troops who’d fallen sick in hospital at Blackboy Hill faced the dire prospect of a Christmas dinner cooked by someone who had just learned to boil water! Instead of having them face this threat she sent up a veritable feast, fit for a king, for not just the patients but the Medical Corps who cared for them, as well.

Beavor, approaching 60, did not seek to renew her lease when it expired in November 1919. She sold at auction all of the hotel’s original magnificent furnishings, including four pianos, oak bedroom suites and floor coverings, even the beer pumps and ice chests. Beavor then retired to Victoria where she died in St Kilda in 1929, aged 69.

Beavor’s lease was taken over by Victorian couple James and Elizabeth Paxton, friends of Nathaniel Harper. James was London-born, and though he initially established himself as a shipbuilder in Albany, he was soon a successful goldfields businessman specialising in diamond drilling. Elizabeth had previously been in service at Melbourne’s Menzies Hotel and was a superb cook and well-experienced caterer. They moved in with their daughter, Elsie (then 14), and son Roy (12).

Almost immediately, however, they were embroiled in a war with angry trade unionists, said to have been led by Hugo Throssell and (his wife) Katharine Susannah Prichard, advocating that the Paxtons’ employment of Chinese cooks in the hotel’s kitchens was against the White Australia Policy, then in place. Intent on forcing the Esplanade Hotel to become a ‘white house’, they picketed regularly and held enormous demonstrations which harassed both management and hotel patrons.

“Mr Needham repeated his statement that Chinese were employed at the hotel, he having seen and spoken to them personally in the kitchen. On the motion of Messrs Millington and Hogarth, the following resolution was carried without a dissentient voice:

That this meeting of citizens of Perth views with alarm and detestation the attack on trades unionism by the management of the Esplanade Hotel, and the violation of the White Australia policy, by the employment of Chinese to the exclusion of white workers in the dispute. Mr Millington said he believed the resolution would have the effect of impressing the management with the force of public opinion, and result in the displacing of the Chinese by white workers.”

Westralian Worker, 20 May 1921

The Paxtons, adamantly supported by Harper, refused to give in. They kept their Chinese staff and continued operating as normal.

Elizabeth’s high standards were soon apparent in everything from the fine linen on beds and tables, fine food served on fine china with highly-polished silver, and beautiful fresh flower arrangements. Emily McCurran, head housekeeper of the Esplanade Hotel and in residence for more than 40 years, reinforced these high standards, ensuring everything was exactly as expected. Elizabeth inspired fierce loyalty in her staff and customers alike, ensuring a strong, happy service team and satisfied customers who regularly returned. The magnificent hotel under quality management was the ideal marriage, and in December 1927 the Paxtons bought the Esplanade from Harper; the sum undisclosed.

With nearby hotels advertising room rates of between £4/night or £20-25/week, the Esplanade’s charges were not widely publicised; possibly indicating if one had to ask, one could not afford to stay there.

Famous Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova had toured Australia and New Zealand in 1926, and returned to Australia where she stayed at the Esplanade Hotel and danced at His Majesty’s Theatre in Perth in July 1929. Two years later she died in the Netherlands from pneumonia and pleurisy.

Recipes for meringue and cream cakes were widely published in Australian and New Zealand magazines from around 1927 but in 1935, the year after James Paxton died, Elizabeth Paxton asked her chef, Bert Sachse, to devise a really special dessert. Sachse was known to read the cooking sections of women’s magazines for inspiration, and there was a prize-winning recipe for meringue cake submitted by someone in Rongotai, New Zealand, in Women’s Mirror magazine published in April 1935.

In One Continuous Picnic: A Gastronomic History of Australia, Michael Simmons states “Bert Sachse experimented for a month. ‘I had always regretted that the meringue cake was invariably too hard and crusty, so I set out to create something that could have a crunchy top and would cut like marshmallow’.”

With the inspired addition of cornflour, he achieved the desired consistency and according to Paxton family tradition, when Elizabeth Paxton tasted Sachse’s creation, she deemed it ‘as light as Pavlova’. The legendary dessert was born - but there is fierce opposition to this legend from New Zealanders who claim their invention of the same dish. Simmons’ research found there were recipes published in 1929 named ‘Pavlova Cakes’ and “the ingredients were roughly those of a pavlova, but it was not the pavlova as we know it, because the mixture was baked into three dozen little meringues. It seems to be a coincidence that this New Zealand cook was also impressed by the ballerina’s lightness and whiteness ... We can concede that New Zealanders discovered the secret delights of the large meringue with the ‘marshmallow centre’, the heart of the pavlova. But it seems reasonable to assume that someone in Perth attached the name of the ballerina …”

In 1937 Elsie married Reginald ‘Peter’ Plowman, a dashing, divorced, Tasmanian-born yachtsman, businessman and friend of Errol Flynn. After a honeymoon in WA’s south west, they moved into an apartment in Ngapara Flats, Malcolm Street, Perth before moving to Lawson Apartments, closer to the Esplanade Hotel.

In May 1939 their son Billy was born and Plowman, who regularly raced his yacht Thera to Rottnest, took a four-year lease of the Rottnest Hostel and Tea Rooms (now Rottnest Lodge) that July. He borrowed a small fortune to update the facilities, hire-purchased luxury furnishings from Boans, and proudly opened to bookings in November.

Seven months later, the army commandeered the Hostel and Tea Rooms without compensation, leaving Plowman to service loans and ongoing hire-purchase expenses without the means of earning his anticipated income. Elsie, as guarantor, soon received writs of demand. Facing bankruptcy, in January 1941 he launched High Court action against the army, resulting in a small settlement of £378. In February he joined the navy and Elsie and Billy moved into the Esplanade Hotel. The next month, Plowman sailed for England at the rank of lieutenant. Their second son was stillborn, here, in November.

Plowman returned in December 1944 having distinguished himself in ordnance clearance and disposal, clearing harbours, waterways and beaches of mines, bombs and booby-traps. In his luggage were letters from an English girl which, when Elsie found them, led to their separation and, eventually, divorce proceedings in 1947. In the ensuing newspaper coverage it was revealed Elsie had had to buy her own engagement ring, support her husband financially while he was away at war because he found his officer’s salary insufficient, and keep herself and Billy throughout the marriage. Her divorce was granted in 1948.

Two years later Elizabeth, much-loved and extremely well-respected by all who knew, stayed with, and worked for her, died aged 74. Elsie and Roy were joint licensees until Roy died prematurely in 1957 aged 49.

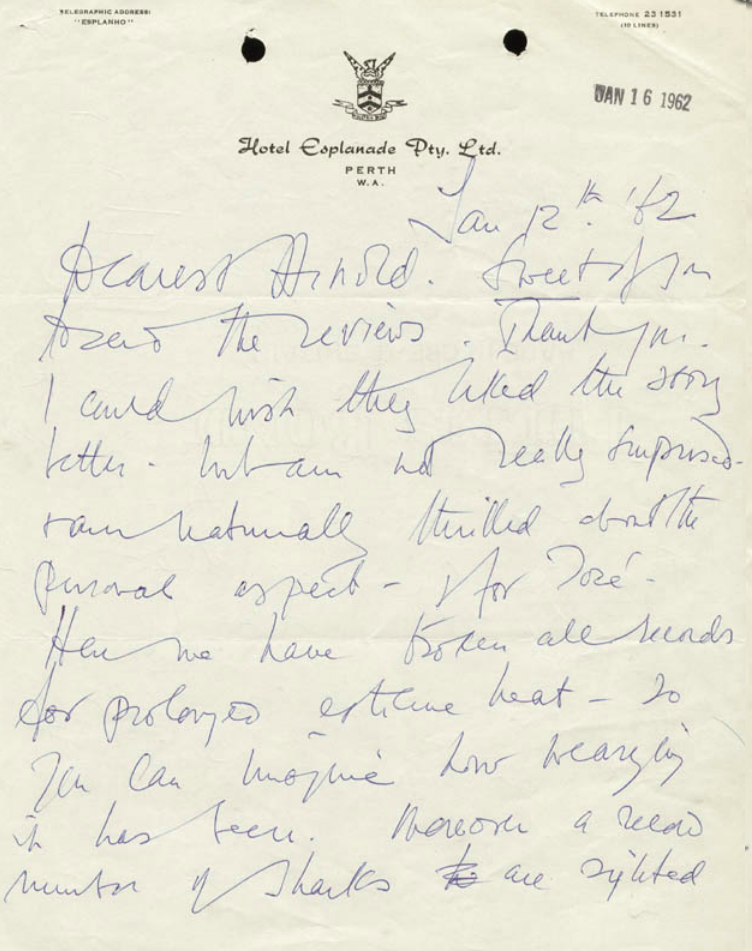

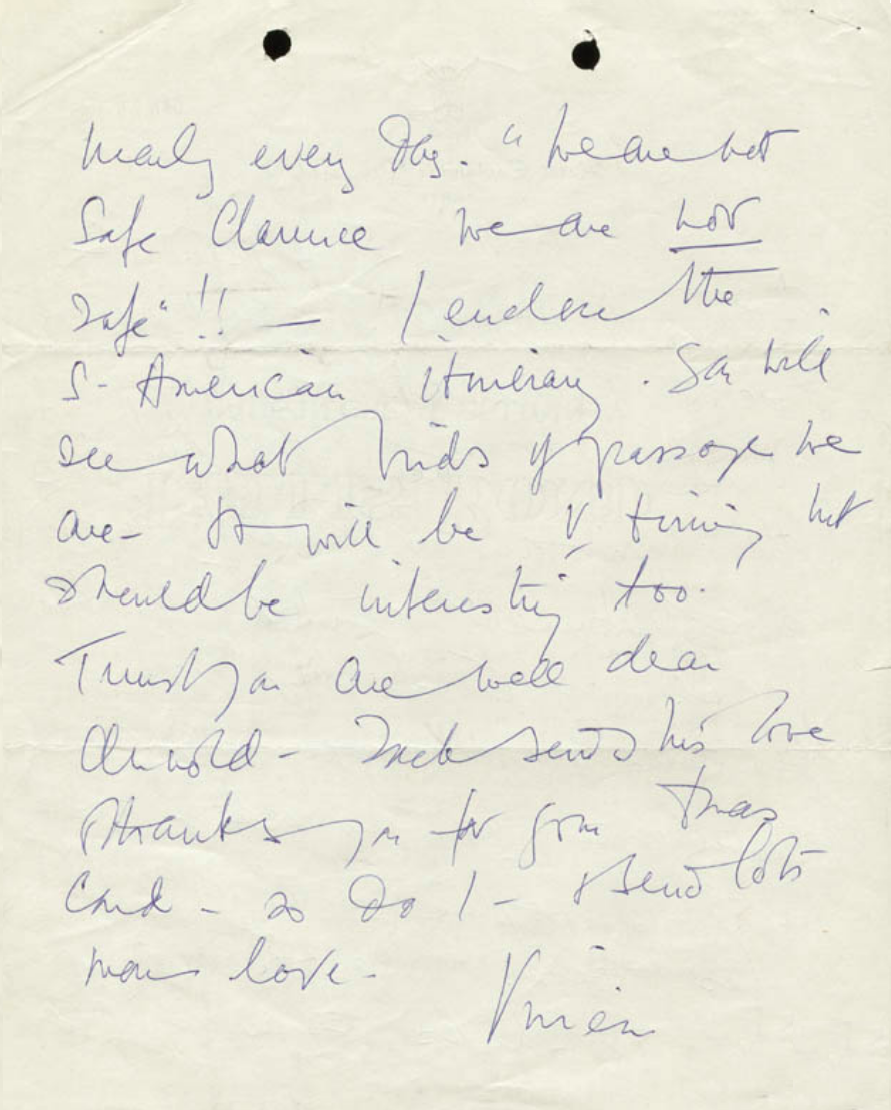

The Esplanade Hotel was still the setting for not only Perth’s high society events, but the destination for visiting stars of stage and screen; most notably, on several occasions, Sir Laurence and his wife Lady Olivier, better known as multiple Academy Award winner Vivien Leigh. During a later visit over the summer of 1961-1962, Lady Olivier wrote to a friend about the insufferable heat and expressed her alarm at the number of sharks sighted here each day, writing dramatically “We are not safe, Clarence, we are not safe!!”

“Comfort was paramount at the Esplanade… She provided a home away from home for prime ministers, ambassadors, musicians, dancers, actors, submarine commanders, financiers and golfers. Many became friends; some, like Dame Pattie and Sir Robert Menzies, were regular visitors. Elsie never drank in the public rooms, but in private proved a generous hostess and a discreet confidante.”

Australian Dictionary of Biography

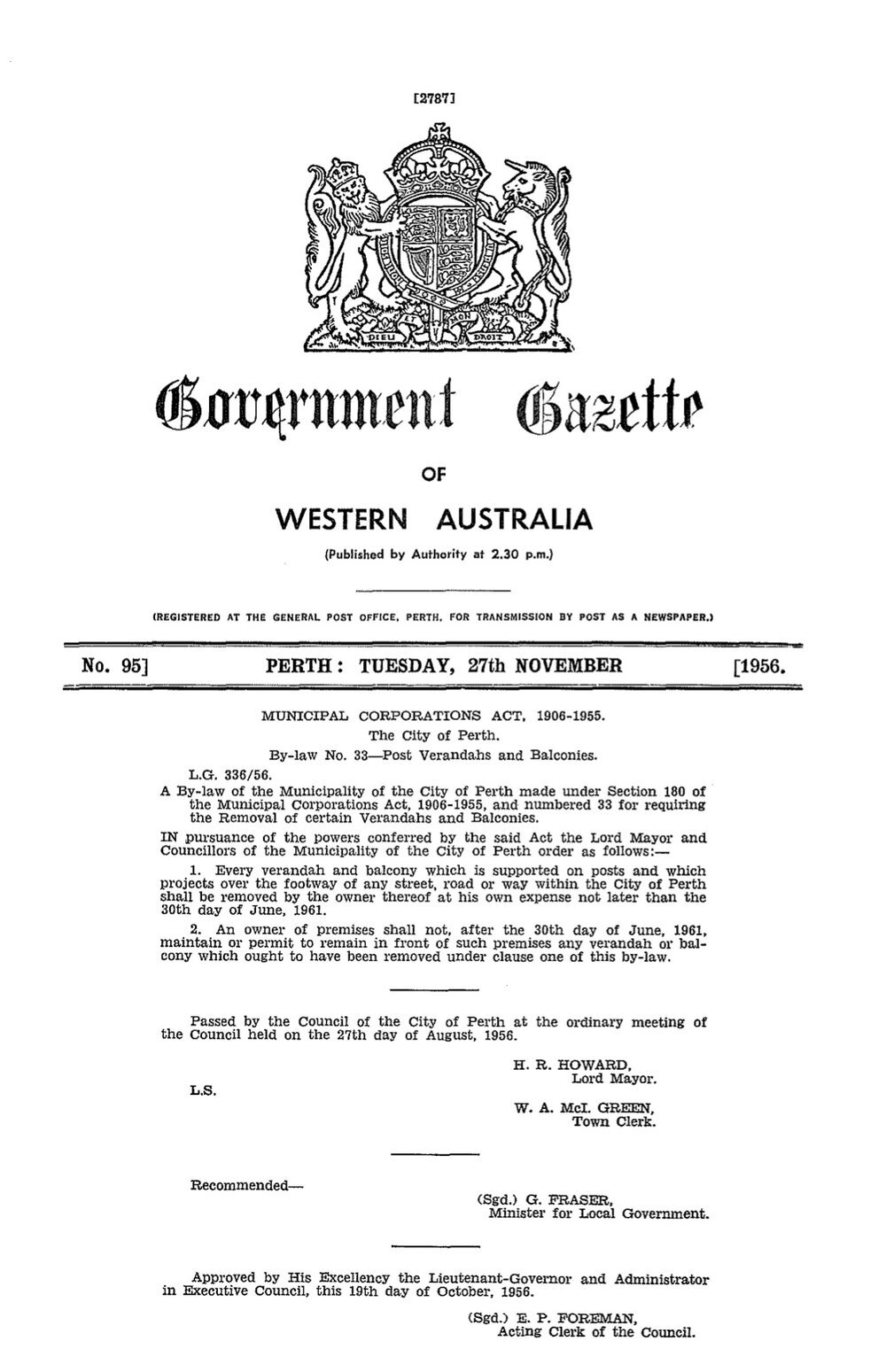

In 1960 Perth City Council introduced By-law 33 which demanded the removal of post-supported verandahs and balconies of hotels throughout the city. This by-law was said to have affected nine hotels, of which six complied by 1962. It was said the other three were the Newmarket Hotel on Pier Street, which closed its doors at the end of that year, the Federal Hotel, which was owned by the Public Works Department and demolished with the construction of the Mitchell Freeway ten years later, and the Esplanade.

Elsie knew her hotel would look vastly different without its magnificent verandahs and refused to comply. With the support of prominent architects like Marshall Clifton and experts who also claimed her verandah was the world’s best known, she launched Supreme Court action against the Council.

Late one night during proceedings, a car veered off the Esplanade and hit one of the verandah posts. Elsie, ever-resourceful, organised its repair before daylight, lest the Council use it as an excuse to proceed with the order.

Elsie won her action against Perth City Council in July 1963 and the Esplanade Hotel was said to be the only Perth hotel allowed to retain its verandah, but the Great Western (Brass Monkey) also retained theirs.

Destruction

Elsie Plowman sold the Esplanade Hotel to developer L J Hooker in 1969 and the building was classified by the National Trust on 2 June 1970.

Simmons continues, “The National Trust gave the building its A-rating, ranking it as one of the state’s most vital structures. The Bulletin commented ‘The three-storey brick building breathes colonial opulence and the grand days of gold… Now the brash days of nickel are here and the Esplanade must yield to steel and concrete’.”

“...I personally regret very much that the Hotel Esplanade has to go. One cannot help but to wish that the community as a whole could be rallied to muster sufficient support to save one of the most beautiful buildings in the city.”

Eric Sabin, Town Planner, Perth City Council, from City of Light, Jenny Gregory

“A last ditch attempt by Prince Leonard of Hutt River Province to dismantle the hotel, salvage all reusable materials, and rebuild it on a site in his breakaway state, where it would become the administration centre for his pseudo principality, also failed.”

City of Light, Jenny Gregory

Despite protests, its National Trust listing, and slightly mad ideas to save it, the beautiful Esplanade Hotel was demolished in November 1972.

Simmons continues “Three years later, when for the thousandth time he passed the site and saw just a hole in the ground, newspaper columnist Kirwan Ward had reversed his opinion: ‘For years it had lent character, dignity and charm to a city that can do with all three… but then came the developers with dazzling visions of soaring towers and thunderous cliches about the inevitable march of progress’. What replaced it? There was the ‘New Esplanade’ next door, but incredibly, a decade later, the site itself was still just a hole in the ground. You never know, Perth’s ‘city fathers’ might yet be sorry that they let some strange economic logic pull down a lively old monument where the pavlova was named.”

With the site still empty Elsie Plowman died in 1978, aged 72. It wasn’t until the early 1980s the 20-storey Griffin Building, now the BGC Centre, was constructed with three levels of basement parking. The New Esplanade Hotel stands on the adjacent block to the east.

By Shannon Lovelady

Story from Demolished Icons of Perth